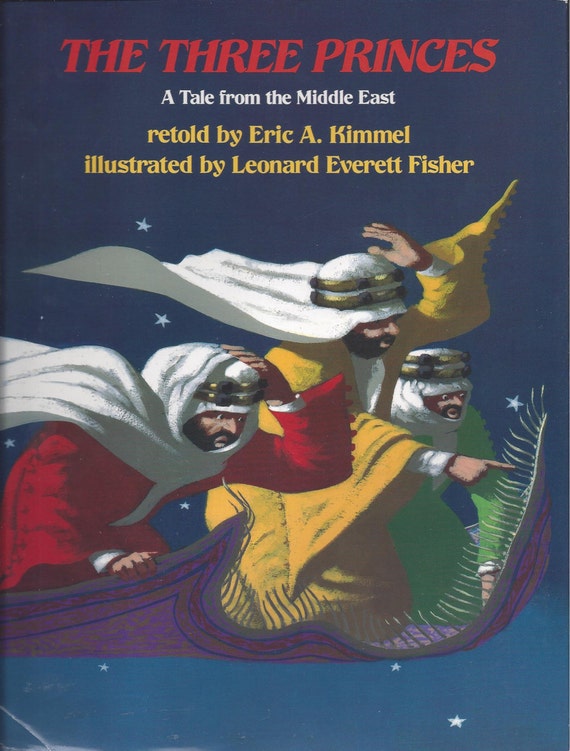

Title: The Three Princes: A Tale from the Middle East

Retold by: Eric A. Kimmel

Illustrator: Leonard Everett Fisher

Publisher: New York: Holiday House, 1994

ISBN: 0-8234-1115-X

Plot Summary: A wise and beautiful princess must choose

between three suitors: Princes Fahad, Muhammed, and Mohsen. Each prince is an

acceptable match by bloodline, but although the princess likes Mohsen best, he

is poor and her counselors do not see Mohsen as being the preferable partner.

Being wise, the princess must base her decision on more than affection.

Therefore she send the princes on a quest to find a great wonder and present it

to her in one year’s time—giving Mohsen the opportunity to bring something that

will demonstrate his worth to her government. While they are absent the

princess becomes deathly ill. Working together and using the wonders they have

discovered, the princes heal the princess. Although all were involved in her

recovery, Mohsen sacrificed his wonder while Muhammed and Fahad retained

theirs. Thus proving his merit, the princess and Mohsen marry.

Critical Analysis: Kimmel and Fisher adaptation of “The

Three Princes” captures the essence of the ancient Arabian world and places it

in our hands through this picture book. The simple plot—a quest to win the hand

of a princess—is made extraordinary by one character, a wise and beautiful

princess. She is a strong and subtle leader of her kingdom, able to juggle her

heart and her government’s concerns, articulated through her chief minister the

wazir. Her personality and power dominate the story; the princes wooing seem

commonplace by comparison. At the beginning of the story Prince Mohsen is prominent

only because he’s the one she loves. By the end of the story Prince Mohsen’s

claim on the princess is still her love for him because although he used up his

wonder in healing her, there is no indication that the other princes wouldn’t

have done the same.

Kimmel’s text is formal, but not stiff or meager. The story

is told as matter-of-fact, even the existence of the magical wonders collected

by the princes does not provoke excitement in the reader. The illustrations

support the mildness; only the scene depicting the princes flying on a carpet

provides any sense of movement or urgency.

Oddly, the calm consistency of the text and illustrations is

exactly what the story needs. It evokes the unchanging desert in which the

story originates. The illustrations suggest the sand—concurrently smooth and

harsh. The chalk medium allows Fisher to smudge and obscure details as well as

stipple shadows that seem to be made of black sand. The primary cultural

markers are the robes worn by the characters and a crescent moon and star in

the night sky.

Most importantly, the tale brings us to a people wise and

peaceful. The universality of the themes—wisdom, sacrifice, and cooperation—are

appropriate and necessary to all cultures.

Reviews and Awards:

“Kimmel's sprightly retelling of a Middle Eastern folktale and Fisher's

ambient artwork shimmer with wisdom and magic.”--Publishers' Weekly

“A smooth,

accessible adaptation, much enhanced by the spare, powerful art.”--Kirkus Review

Eric Kimmel has received

numerous awards for his books, including: Caldecott Honor Medal, Sydney Taylor

Picture Book Award, National Jewish Book Award (twice), and the Naylor Award.

Leonard Fisher has

received numerous awards as well: 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Painting, Arbuthnot Citation,

National Jewish Book Award, Christopher Medal for Illustration, and many

others.

Discussion Prompts: (adapted from Hampton-Brown teacher guide)

Is it better to work together or alone?

When?

How would the

three princes answer this question?

The three princes have

to work together. Have you ever had to work in a group to solve a problem? What

did you like about it? What did you not like?

What if only two of the

princes agreed to work together and the third did not?

Lesson Plan about Middle

Eastern Folk Tales:

http://www.csames.illinois.edu/documents/outreach/Middle_Eastern_Folk_Tales_Lesson_Plan.pdf

Created for course 5603.21 at Texas Woman's University

Created for course 5603.21 at Texas Woman's University